How Interest Rates Affect MRR

We all hear, "get MRR." MRR is Monthly Recurring Revenue - the money we are paid regularly by our customers, so they continue to receive value from our services.

Why is MRR valuable? The belief is that a recurring revenue model will create an automatic customer: someone who will pay for your service for years on end.

This model is valuable in 2021 in a way it was not in, say, 1981 because of historically depressed interest rates. Interest rates tell us how much a dollar in the future is worth compared to a dollar today. Consider the aphorism, "a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush." The bird in the bush will enter my hand later but has less value (in this case, half) because it is at a point distant.

Putting numbers against that, the value to me of a dollar today is a dollar! But the value of a dollar that I am guaranteed to get a year from today is equal to a dollar minus how much it would cost to borrow a dollar for a year. We call this cost a "discount rate." The idea is that I can borrow a dollar, pay interest, and return the dollar when the future dollar is available. So if it costs me, say, 10% per year to borrow, then the promise of a dollar in a year is worth $1 - $1 * 10% = $1 * (1 - 10%) = $0.90. Two years from now, the cost of a dollar is $1 * (1-10%)^2 = 0.81. And so on.

An interesting consequence of this math is you can calculate the value of getting a dollar per year forever. The formula is that at a 10% interest rate, the present of getting that dollar every year forever is $1 / 10% = $10.

You can see that a lower interest rate would make that income stream more valuable. If the interest rate were 5%, the value would be $1 / 5% = $20. If the interest rate were higher, it would be less valuable.

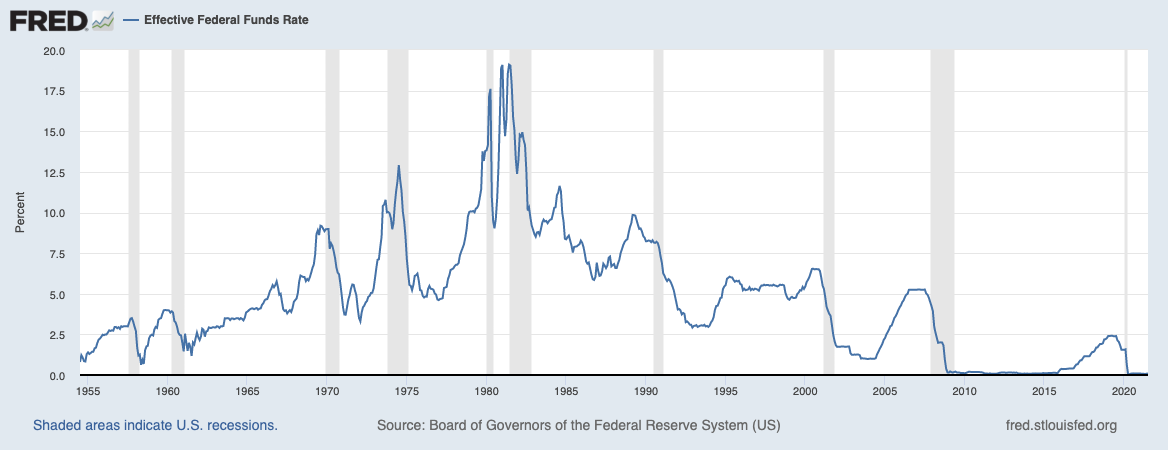

That 10% is easy for a demonstration, but how much is that discount rate today? A good way of tracking interest rates over time is the Federal Funds Rate - the price commercial (big) banks charge to lend money from other commercial banks overnight. The costs of different financial products tend to move up and down, layered or multiplied over this lowest interest rate.

Let's look at this historically. In the 1980s, the fed funds rate was higher: between 6% and 17%. In the 1990s, the rate was between 3% and 6% - more moderate. The rate crashed to near-zero in the wake of the dot-com crash and 9/11, creeping back to 5% right before Lehman Brothers went bankrupt.

Since the financial crisis of 2008, the fed funds rate has stayed between 0% and 2.4%. Wow! We haven't seen an era of rates this low since the early 1960s. Here's a chart of how it looked since, including the periods described above:

When interest rates are low, a dollar in the future is much closer in value to a dollar today. One is more willing to accept a stream of income over time because that money is closer in value to just having most of that money today.

On the other hand, when interest rates are high, the future income is worth far less - we want money today! Furthermore, when interest rates are higher, there is a more significant difference between the cost of capital of large businesses vs. small businesses. Big companies which can access the corporate bond market see their rates go up some, while small ventures that need to use bank loans see them go up a lot more. This difference in access to capital creates a significant spread in the time value of money between a big company and a small company. From the point of view of a B2B startup, this can be important.

Let's take an example where interest rates are high, and the access to capital means a big swing between them. The big company would see a payment stream of $100/year at 10% interest to cost them $1000. The startup with a 20% interest rate would see that same annuity worth $100/20% = $500. That means the startup thinks they are selling $500 of goods while the big company pays $1000 for that same subscription. That's a misalignment.

As a result, the startup might instead sell a perpetual or long-term license for a fixed up-front fee (say, $750). The big company buying it could finance that by getting a loan to pay for it over time. The buyer receives an effective discount because $750 is less than $1000. The seller has a higher price point than the future value of the revenue stream. Everyone wins!

This up-front capitalized pricing model is how a lot of software got sold in the previous millennium. Interest rates played a significant role. The plummeting cost of debt after the dot-com crash of 2000-2001 was a key financial factor in Salesforce realizing that the software-as-a-service pricing model could have a competitive advantage. He could afford to sell subscriptions because that future money was worth almost as much as the current money, even to his smaller company!

This low-interest-rate era gave us its first hints in the early 2000s but has been with us in a much more consistent, extreme form since the Great Financial Crisis. Cryptocurrency enthusiasts and other monetary bears keep on shouting that this trend cannot last. They believe bottomed-out interest rates will eventually unleash inflation, which will drive up interest rates, and the only happy people will know how to pronounce HODL.

I do not have any insight as to which way interest rates will move. As Yogi Berra once said, predictions are hard, especially about the future. But thinking about what makes MRR more or less valuable is helpful to any investor or entrepreneur in the subscription economy.

Interest rates are not the only reason subscription customer relationships are valuable, but we should pay attention to them. At a minimum, if they go up in the future, we may find the "recurring" part of MRR going more out of vogue.

Photo by Fabian Blank on Unsplash